Rodney Robinson’s Goal for His Time as National Teacher of the Year? Nothing Less than ‘Saving Lives.’

September 26, 2019

September 26, 2019

By Tom Allen

In the Richmond classrooms where Rodney Robinson has spent his 19-year teaching career, some decisions made quickly and easily in other schools, like suspending a student, must be made very, very carefully. At Virgie Binford Education Center, housed in the city’s juvenile detention center and, before that, at Armstrong High School, some of those decisions can literally mean life or death.

“Suspending kids from school not only lessens the chance they’ll graduate because they’re missing school time,” says Robinson, America’s 2019 National Teacher of the Year, “but you’re also putting them in a horrible situation. You’re sending them back into the streets where they’ve learned bad behaviors, only to learn more bad behaviors.”

These young people often face very limited options and Robinson, a Richmond Education Association member, says it shouldn’t be that way.

Those kids are the reason Robinson sees his time as National Teacher of the Year as a year-long mission, not a victory lap. His objectives reach well beyond the classroom, too. “The real mission is saving lives,” he says.

Robinson got his first experience with Richmond’s young people at Lucille Brown Middle School, where he was hired fresh out of Virginia State University to teach social studies in 2000. “I was 21 years old and in charge of 140 seventh-graders,” he says with a laugh. “I didn’t even have charge of myself at 21.”

Still grinning, he adds, “If your first year isn’t rough, you aren’t doing it right.”

Following that first year, he moved to George Wythe High School and spent two years there teaching and coaching football before going to John F. Kennedy High School, which merged with Armstrong the next year.

Armstrong draws its students from high-poverty neighborhoods and “has its reputation,” says Robinson, but he made it home for the next 12 years. An opportunity at Binford came up in 2015, which coincided with a piece of unsettling news that came Virginia’s way.

“I was hesitant about moving to Binford, but then a report had just come out saying that Virginia led the nation in referring kids to the juvenile justice system,” Robinson says. “I thought I could read books and learn about the school-to-prison pipeline, but what better way to understand than to go into a prison and teach?”

When he arrived at Binford, among the first students he encountered were three he’d failed the year before at Armstrong. “It made me think about what I’d done to cause them to end up here,” Robinson says, “and I began to understand that there’s a real connection with poverty. We’ve criminalized poverty in our country. It became a moment of real reflection and led to a wholesale change in my approach to teaching, students, discipline, and grading. Really, it changed my whole attitude about education.”

Binford has been the perfect place for Robinson to put that attitude into practice. “Here, we don’t see thugs or criminals—we see kids who, with proper motivation can turn their lives around,” he says. “I tell my kids they’re here for a reason, that sometimes you have to sit down in order to plan out your future. When they’re in the streets, they’re in survival mode. So, when they come to us, we take a moment to say reset, regather yourself, and let’s focus on some things that are important in life. We’re going to be here to help you achieve whatever goal you want to achieve. Detention is only a temporary setback to get where you need to go.”

Teaching at Binford has also solidified his commitment to a wholehearted “kids-first” approach. “I work to build relationships and get to know students,” he says. “That’s more important than any lesson plan I’ll ever have.” That attitude extends beyond class time, as Robinson frequently spends time with students in the residential area of the center known as the pods.

Juvenile detention is, though, an undeniably difficult and often frustrating work environment. The seemingly insurmountable challenges his students deal with every day, in school and out, weigh Robinson down at times.

“Secondary trauma is a lot,” Robinson told the audience at a recent speaking engagement. “When I hear about a violent crime involving people under 25, I often know the victim, the perpetrator, or both. Once, when my wife told me about an incident in which a young child was shot, my first thought was ‘Yeah, that happens.’ That’s not a normal response. I began looking into some therapy for myself.”

But, he says, his Binford experience has emboldened him: “It’s given me new insight for what our kids need and the more I learn, the more I can advocate for them.”

Advocacy is what the year ahead is all about for Robinson, and there will be several topics front and center as he steps out on his new national platform.

“I’m passionate about educational and cultural equity,” he says, defining educational equity as providing the necessary resources to all students and cultural equity as students seeing and being influenced by more educators who look like them and value their cultures.

“In our country, students of color make up 50 percent of all our students, but the teachers are still 80 percent white,” says Robinson, who grew up in the predominantly white school system of King William County. “I didn’t have many teachers or people who looked like me who told me I could be and do whatever.”

Today, he sees the impact of that kind of experience in his work at Binford. “A lot of times my students have had teachers who referred them there because of just simple cultural misunderstandings,” he says. “I just want to educate as many people as possible on how to value and love students of all ages, backgrounds, and races.”

Robinson intends to use his year to affect education policy, too: “I just want to get in the room. That’s where the economic equity comes in, just speaking to school boards, city councils, state legislators, even federal legislators, talking about what kids need and making sure that funding in education is equitable.”

There are mountains to climb in our public schools. “The achievement gap didn’t just happen, it’s the result of a system,” Robinson says. “It’s time to start pointing out some of the things in the system that lead to it and to the gap in graduation rates, the gap in students going to college. It’s time to start addressing those things and I want to speak about it. I feel my voice is needed.”

He’d also like to promote an often-overlooked potential alliance. “One of the things I’ve learned in Virginia is that some of our urban and rural areas are facing the same issues—the same poor infrastructure and the same lack of resources for teachers and students,” he says. “It’s about time we started partnering together to advocate for what our kids need, because they need the same things.”

Robinson relishes being the teacher role model he didn’t have enough of growing up and will push hard to encourage young men and women of color to enter the profession. Actually, he could probably rest on his laurels already—some 20 of his former students are now teaching and others have pursued careers in social work.

Doron Battle, now a special education teacher at Richmond’s George Mason Elementary School, had Robinson as an 11th-grader. “He knew his stuff,” Battle says, “and he had a way of making history come to life. He was also super fair, and he looked and talked like us. We gave him 100 percent. He was the perfect example for me when I was thinking about being a teacher.”

“I often tell young educators of color to get comfortable in uncomfortable spaces,” Robinson says. “Sometimes when you go to professional development or a workshop, you’ll be the only person of color in the room. Embrace that, be yourself, and speak up for what your kids need. If you do that, other people in the room will speak up for what your kids need, too.”

Robinson points to statistics that show reduced referrals to special education and absenteeism and increased parental involvement when students of color have more teachers of color.

He also sees another glaring obstacle for potential educators of color, especially men. “Black and Hispanic males are often the students who have the most negative experiences in school,” he told the same recent audience. “No one wants to go back to the site of their trauma. We need to help them have better school experiences.”

In the end, Robinson is optimistic about the future, and the source of his hope is, as one might expect, the kids. “My faith isn’t in our leaders and politicians,” he says. “It’s in my students. I encourage them to speak up. They have powerful things to say and we have to get out of their way and let them say it.

Robinson has been a card-carrying VEA member for his entire career. “Being a member has been really helpful to me because it taught me how to advocate not just in the classroom but in political circles,” he says. “As you begin the journey of advocacy, you’ll find yourself in a lot of rooms with a lot of powerful people but thanks to the tips and training I’ve gotten from VEA, I feel very comfortable in those rooms telling the stories of my kids and what they need. Plus, I’ve made lots of connections and heard lots of ideas.”

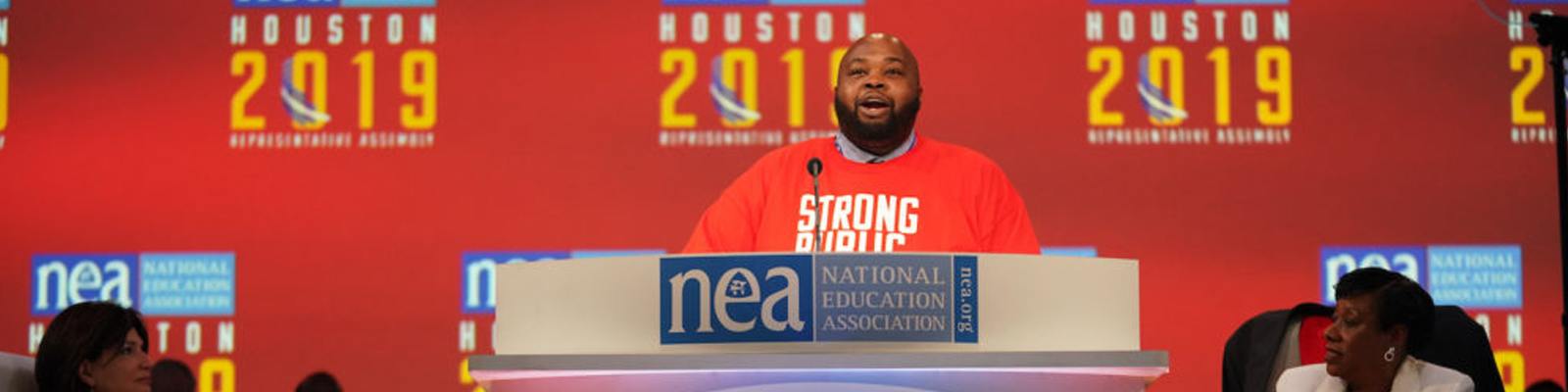

This summer, he addressed the 6,000+ delegates to the NEA convention in Houston. “I just told the story of my kids, the things that were on my heart,” he says. “I didn’t know how well it was received until afterward when a lady came up to me and said she’d been coming to the convention for 40 years and no one had said the things on stage that I said. So that let me know I was on the right track.”

VEA President Jim Livingston has no doubt about the track Robinson is on. “I can think of no one better suited to represent our nation’s teachers,” he says. “The love he shows every day for his students is an inspiration not only to them, but to their families, his colleagues, and the entire community. I know he’s changed countless lives.”

You might expect Robinson to have been told he was the National Teacher of the Year in some kind of elaborate ceremony in his classroom or in Washington, D.C. You would be wrong.

“I was on my way to Whole Foods and got a call as I turned into the parking lot,” he says. “I thought I’d forgot to turn in something because we weren’t going to hear anything for two more weeks. But they told me and I went through the gamut of emotions—tears, celebration—I’m pretty sure the guy in the car next to me thought I was having a mental breakdown. It was a very emotional moment, and also very humbling because I was being given a big opportunity. Once I realized the seriousness of it, I had to think about how I could take advantage of it and how I could advocate for my kids and for teachers all over the United States. I think I came home with just grapes. I’d forgotten everything else that was on my mind.”

Allen is editor of the Virginia Journal of Education.

According to a American Library Association survey, 67% of voters oppose banning books from school libraries?

Learn More